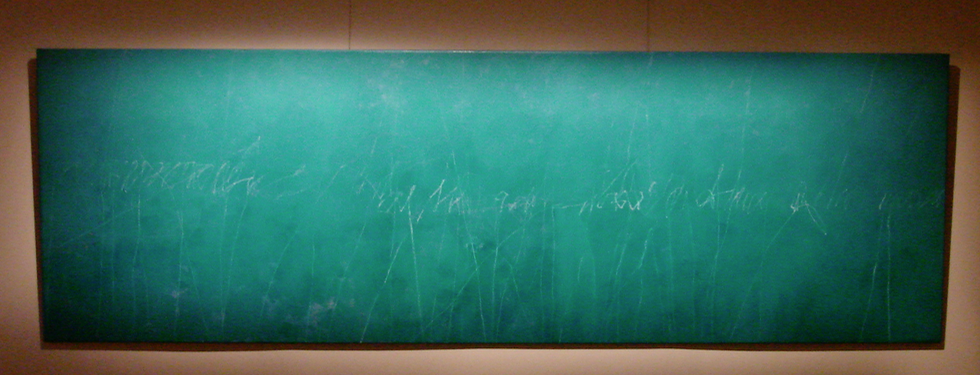

Francisco Mejía-Guinand – Paintings, 07.11.2008 – 10.12.2008 at CLAIR, Munich

Francisco Mejia-Guinand, born 1964, is a Colombian abstract painter and arquitect who is not easy to fit into the current scene of non figurative art. He used art concepts to make arquitecture and arquitecture to make his inner art work.

Caligraphy I is a series that was shown in München, november 6, 2008 was his first solo exhibition. Caligraphy I is a very personal work: “It is very physical ii is not a technique or and ideology it is a form of pure expression” (MG).

As Juan Manuel Bonert express in the text “Geometry and Mist” for the presentation of MG´s work at the es Baluard collection in Palma the Mallorca in 2006, “Working intuitively on large surfaces, with a poetic that is an heir to the ‘fifties” painters and charcoal drawings that structure the surface, MejiaGuinand (who, like a good number of contemporary artists, has an arquitectural degree and has work in that profession) slowly constructs a closely wowen space, an infinite mesh, a tangle, a labyrinth which prompts the gaze, and the soul, to lose itself in it. Geometry, but obviously with no straight lines nor flat colors; nothing of “program”.

A Conversation with Francisco Mejía-Guinand

From Architecture to Painting

Question: Francisco Mejía-Guinand, you are an artist and an architect, you’ve taught architecture and art history in the Columbian capital of Bogota. You’ve now dedicated yourself entirely to painting. Why?

M-G: After I completed my studies in architecture, I worked for two years as an architect. What most interested me about architecture – and still does – is the integration into a creative process that is very similar to the process of creation in the world of painting. For me, architecture is a form of art, the implementation of which was not very clear in the activity I was to be conducting, and so I began to evolve into a painter. I have conducted many projects where I attempted to bring art and architecture together in public places and buildings. I feel there is a great deal of importance in the dialog between what’s public and private.

On the Search for Balance

Question: Is there then an ideal space for art?

M-G: For me it’s about bringing the architecture and the city together in harmony with a personal, private space. I long for a work that connects the two worlds, the public and private. For my artistic activity, my education as an architect is always present – even in the creative process of my paintings. By painting, I am always looking for an order, for a balance. It is a conceptual search that is similar to those in architecture and in city planning: the human search for harmony, for a harmonic balance of the human senses.

Question: You spoke of the search for an order in the interior world…

M-G: Yes, this relationship, the balance between our environment and the interior world is that which we ultimately call harmony. It’s very distinct in music and comes clearly to life. When something is harmonic, then there’s a perfect balance between the interior feeling and the way in which this is extraverted.

On Painting as a Language

Question: In many of your pictures, lines and strokes disappear into a diffuse haze, a little like dreams after rainy nights…

M-G: For me, painting is like a language, and in this language of painting there are special codes, just like in the world of architecture. We architects draft an ideal world based on lines and drawings that end up being reality at the end of the day. I believe that these lines and codes are also components of a language, however that of an encoded language. This language, in the form of lines and scribblings that sometimes appear to be insinuations to our written language, is however only slightly accessible. I try to convey the sensuality of these lines in my paintings.

Question: You prefer large formats and you once indicated that you paint with your entire body. Why?

M-G: The large format canvases demand a relationship much like when dancing. With that, there isn’t just the movement of the hand, but rather that of the entire body around the canvas. The movement of the body over the entire canvas with the corresponding resources allows for this form of expression. The speed with which I work is what allows this line routing. In addition, I just feel much better working with large format pictures.

On Tradition

Question: For many artists, the embeddedness in a tradition right on up to an artistic flux is an important element in their creative development. How do you see yourself?

M-G: My painting and my conceptual education as an artist and architect certainly are related to art history. The adoption of art history is an important topic for me. The Florentine artist Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) and his work on the battle of San Romano even became an art obsession of sorts for me.

Question: You once said, “When I paint, I forget everything around me.” Should that mean that you transcend everything that you’ve learned? Or is painting an activity that allows your workday to take a step back?

M-G: It’s both. On the one side, I have a great respect for tradition. Yet when I begin to work, all of the concepts and values I’ve learned that are a part of my knowledge of history take a backseat. Then, on the canvas, elements can appear that protrude from my subconscious.

On Art in the Globalized World

Question: The world in which we all live today distinguishes itself through an unbelievable pace and volatility. What priority does art have for you in the world of today?

M-G: 50 Years ago, the large metropolises of the world seemed to be in a contest with each other to be the Mecca of art. Today, I believe we can no longer speak of an individual, concrete place that serves as the Mecca of art due to the speed of communication in the virtual worlds. Every capital possesses a large cultural heritage, a line of values and works that wish to be passed along. There isn’t just one single tendency, but rather a large number of drifts. However, art remains the most important manifestation of a society for me. It is an idiosyncrasy of our post-industrial society that this is complex and has brought forth parallel diverse cultural values. I fit in well with society and in the time in which I live. I attempt to make a contribution to this historical process, for this is actually the rhyme and reason of an artist, to provide a witness account of the day and age he or she is experiencing.

Question: How much have you been shaped and characterized by your environment, by your homeland of Columbia?

M-G: The origin of an artist was an important factor a few decades ago. I think that the circumstance of being born in a specific country isn’t so decisive any more because we currently have the possibility to travel through the world and to get to know various aspects of various societies. In my own very personal case, although I was born in Columbia, and as such, am a Columbian painter, I travel a lot around the world. I am open for new approaches and the new cites that I visit. However, I have never tried to apprehend topics with socio-political or local aspects, allowing the reality of my country to enter my art. My approach is an art-historical, an art-immanent one – for me it’s solely about plastic aspects, about esthetic dimensions, in which I can’t integrate any socio-political observations. Geography is a bit more influenced by the change in climate, the exchange of colors that have an impact on me. It’s about where I paint: in Palma, in Greece or in Bogota. That changes the pigments – the colors – in my pictures a little bit.

On Role Models, Picture Titles and the Love of Colors

Question: Why is it that some of your works do not have a title?

M-G: A title already embodies a reference point that immediately influences the viewer in his or her observation. I try to allow the beholder to have complete freedom in taking in a feeling for the picture that I am approaching them with.

Question: Your favorite painter?

M-G: Without a doubt, I have a great affinity for Picasso – not just for his work, but rather for his personal life. I like the way in which Picasso grasped his life and his work, and how he understood being a person of his epoch.

Question: Speaking of Picasso… He supposedly said, “If I don’t have any blue, the I just use red.” Would you also say something like this?

M-G: That’s always the case for Picasso. Every topic becomes a pretext for him to create something. It has been said that Picasso has been the great destroyer of art history, for he has no parameters for his language. He nonetheless searched for and studied the sources of art history in order to even get to this approach whatsoever. That means, in relation to the colors: for him, it doesn’t matter whether he takes black or white, as long as a pretext for creating something is offered.

I’ll tell a little a story in relation to this: the people that normally do not work with colors do not know that colors can also make a person tired. When I paint a lot of red, that makes me tired. White becomes foreign to me, and black too. That is why I paint various pictures parallel to each other. I recover a bit from certain colors by working with other colors.

At the time of the implementation as well as at the time of the reflection, if the picture is complete, then there’s a relation to the observer and also to the physical space, to the corporal environment around you. The works occupy space and change it. They illuminate it or absorb it. That is a very impressive experience. Color possesses the ability to cause spatial change.

Question: And what is your favorite color?

M-G: (laughing). Red. Maybe. Maybe today, but I don’t know about tomorrow…

Question: Are you now completely finished with architecture?

M-G: Not at all. It remains very present. I even believe that at the end of my career, I will create works that include art in architecture. By the way, I received an invitation from some friends, architects, to take part in a project in Bogota. This project will involve the relationship between buildings and city environments via art.